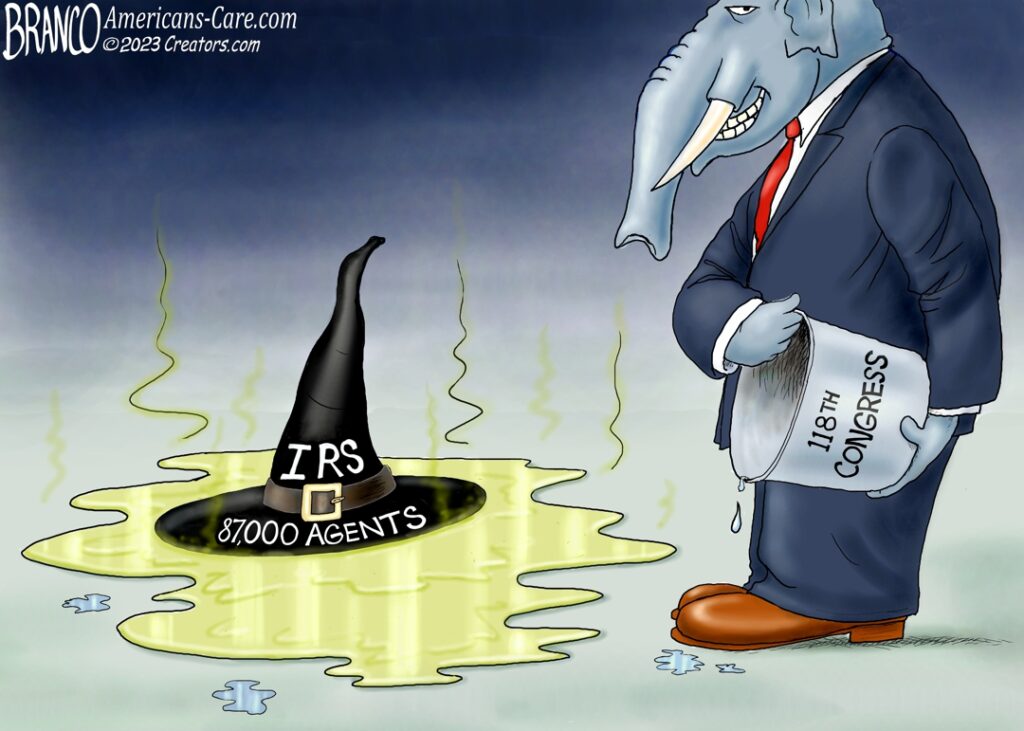

🚨 BREAKING → The House just voted to repeal funding for Biden’s 87,000 new IRS agents.

Every Democrat voted no. Tells you all you need to know.

— Steve Scalise (@SteveScalise) January 10, 2023

The 87,000 IRS agents will not be repealed by the Senate. The days of impotent message votes designed to fuel reelection campaigns are upon us. pic.twitter.com/uLFSKPDxwa

— Joel Berry (@JoelWBerry) January 10, 2023

Joel Berry, Managing Editor at the Babylon Bee, has a shrewd take on politics. He does not believe the House vote to defund the plans for IRS expansion was honest. In fact, he believes that if the GOP had the Senate and white House this vote would never have passed. He claims it is pure theater.

What do you think?

Is it possible or is it theater?

There is much more going on behind the scenes here than the average person understands. The multi-year IRS funding Congress included in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is effectively immune from the normal annual appropriations process. It can be cut directly only in the way House Republicans tried, with a new law that rescinds all or part of that IRA spending plan. How that law fares in the Senate and on the Oval Office Desk can be questioned.

However, this is just the first strike in the battle to reduce spending. It all comes down to Appropriations.

What is the appropriations process?

According to Congressman Danny Davis:

Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 of the Constitution provides that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Therefore, all expenditures for all federal agencies and programs must be approved by Congress and then signed by the President.

About 2/3 of federal spending is “non-discretionary.” This is for programs like Social Security, whose annual costs are already determined by law based on the number of people served and their eligibility. The remaining 1/3 is “discretionary”: this includes areas like defense or education funding, for which the spending is set each year by the Congress and the President.

Discretionary spending bills are generally enacted annually for the next fiscal year. It is a two-part process. Discretionary spending is usually first “authorized” in one bill, and then the actual funding is “appropriated” in another bill – an “appropriations bill.” This mechanism is meant to help control overall spending.

Once funds are appropriated, Congress expects that these funds will be used during the fiscal year for which they are appropriated. Congress must enact annual appropriations bills prior to the beginning of the each fiscal year (October 1) or provide interim funding for the affected programs through a “continuing resolution.” Sometimes, the Congress will combine several appropriations bills at the end of the year and pass them all together as an “omnibus.”

How does the appropriations process work?

An appropriations bill is considered in much the same way as other bills that pass through Congress. It is introduced by Members of the House and Senate, subcommittee hearings are held, subcommittees and committees amend the bills and vote on them, they are considered by the full House and Senate and votes are taken, a conference committee is appointed to reconcile differences between the two chambers’ versions, and the conference report (i.e. the final bill) is then voted on by the House and Senate and sent to the President for signature or veto.

Unlike other legislation however, the appropriations process generally follows an annual timeline. The House generally begins the process with the Appropriations Committee’s subcommittees (one for each of the 12 bills) holding extensive hearings on each of the spending bills. Hearings usually begin in early March, soon after the President’s budget is submitted to Congress.

The House starts voting on appropriations bills in May and seeks to complete this by the August district work period. In recent years, however, many of these votes have not occurred until the fall. The Senate may begin committee work on its 11 spending bills and may even vote on the bills before the House completes its work.

After the House and the Senate have each voted on its versions of an appropriations bill, a conference committee meets. That committee consists of equal number of House and Senate members who reconcile any differences between the spending bills.

The conference committees make the final decisions on bills and reconcile the differences. The conference report is then sent to both the House and Senate for approval. If approved, it is then sent to President. After the President signs a bill, each impacted department or agency reviews the bill, makes the regulatory changes mandated by Congress and begins allocating the funding to appropriate departments and projects referenced in the bill. When there is a direct appropriation to an outside entity, the agency will usually allocate funding to the organization or community in the spring (mid-March through May).

What is the timeline for appropriations bills?

- First Monday in February – President submits budget for following fiscal year to Congress

- February 15 to April 15 – Congress considers and passes a budget resolution

- Late February through late March – House Appropriations subcommittees begin hearings on 12 appropriations bills – begins “marking-up” (amending) bills.

- March through June – Senate Committee considers its 12 appropriations bills.

- June 10 – House Appropriation Committee reports to full House the last of its appropriations bills.

- June 30 – House concludes action on regular appropriations bills.

- By August – Senate and House usually have voted on their appropriations bills. Some bills will have already gone through conference committee, approved by the House and Senate and sent to the President.

- September – Remaining conference committees meet to finalize appropriations bills. They are voted on and sent to the President for signature

- October 1 – New fiscal year begins

- October – If necessary, Continuing Resolutions allow the federal government to continue working under previous year’s budget authority until their appropriations for the current Fiscal Year are approved.

What is an earmark?

In some appropriations bills, the Congress outlines specific projects or recipients of agency funding. The appropriations subcommittees review requests for such project listings from Members of Congress. Relatively small amounts of funding are dedicated directly to such projects, and it is extremely difficult to secure funding for “earmarked” projects because of severe budget limitations. Projects requested by the House (and to a lesser extent the Senate) can receive an appropriation only if there is an authorization law which directly supports the project – in other words, there must be a program in the federal government from which funds can be drawn.

An “earmark” is different from a federal grant. A grant is made by a federal agency directly to an organization, municipality or state from funds which the federal agency has in its budget. Grants are made on a competitive basis usually after a Notice of Funding Availability has been issued. Organizations submit an application by a subscribed due date. Usually the agency will set up a panel of grant reviewers to read and rate the applications. Awards are granted several months after the application is submitted.

Here’s how the IRS cuts could happen:

Later this year, the House will pass an IRS budget with deep cuts in fiscal year 2024 funding. The Senate, by contrast, will fund the IRS at something close to whatever President Biden requests (we’ll probably know the number sometime in February). While the House leadership promises to pass a free-standing bill that funds the IRS, Treasury, and some smaller agencies, the Senate will package all or most of its fiscal 2024 spending bills into a single huge measure.

Then negotiations will begin. The GOP will threaten to threat to shut down the government and, more importantly, its threat to allow the nation to breach its debt limit.

In that environment, it would not be at all surprising to see Senate Democrats agree to trim the IRS budget—not as much as the GOP would like but enough to slow the agency’s efforts to increase compliance and make tax filing easier. (More here at Forbes)